Written by:

Ismail Olajide Abdulrazak

Program Officer, DGI Consult

Background

Limited access to essential healthcare services remains a barrier to achieving universal health coverage (UHC) in Nigeria. This is evidenced by suboptimal health indices, with a high maternal mortality rate of 1,047 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births[1], infant mortality rate of 63 deaths per 1,000 live births, and under-5 mortality rate of 102 deaths per 1,000 live births.[2] The country’s healthcare system is characterized by inadequate resources (human, money, materials) and weak policy implementation. This is further compounded by the inability to optimize available resources to catalyze desired improvement in health outcomes.

Improvement in health system performance largely depends on government institutions’ effectiveness, efficiency, and management capacity to implement key health policies and plans adequately.[3] These institutions play key roles in developing policies, strategies, and plans to mobilize resources while ensuring effective implementation and monitoring for efficient resource utilization. However, management capacity gaps hinder these institutions from effectively implementing available policies and plans, as well as mobilizing and optimizing resources to achieve their core mandates.

The decentralization of health insurance, which led to the creation of State Social Health Insurance Schemes (SSHIS), aimed to improve access to basic and affordable healthcare services. However, the SSHISs have only covered less than 5% of the population in most states. This slow pace of coverage expansion can be ascribed to the managerial gaps hindering the State Social Health Insurance Agencies (SSHIAs) from fully achieving the health insurance decentralization policy goals. Similarly, the State Primary Health Care Development Agencies (SPHCDAs) are confronted with management capacity gaps impeding them from effectively implementing PHC reforms such as PHC Under One Roof (PHCUOR) and Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) that are crucial to the delivery of Minimum Service Package (MSP) and are fundamental to improving health outcomes.

Based on the foregoing, DGI Consult, through the USAID Local Health System Sustainability (LHSS) Project deployed a co-creation approach using an organizational capacity strengthening tripod model to strengthen the institutional capacity gaps of the SSHIAs and SPHCDAs in Nasarawa, Plateau and Zamfara States for improved organizational performance to achieve the objectives of expanding coverage and access to the teeming population of the states.

Approach

A participatory and co-creation approach was deployed to identify capacity gaps and strengthen the institutional capacity of the SSHIAs and SPHCDAs in the 3 states through the following activities:

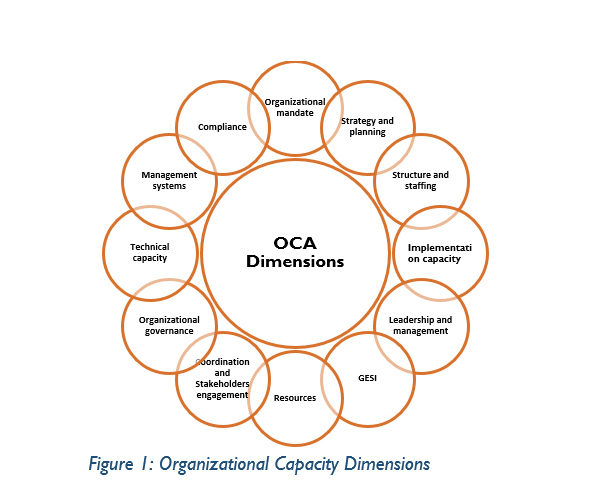

- Organizational capacity assessment: A participatory organizational capacity assessment of the SSHIAs and SPHCDAs was conducted in the 3 states using a revised organizational capacity assessment tool (OCAT) to appraise the agencies’ capacity across 12 broad dimensions (Figure 1)through (i) Desk review of existing documents; (ii) Deployment of an online questionnaire to the staff of the agencies to gain an insight into the agencies’ capacity gaps; (iii) Focus group discussion with program officers and managers; and (iv) Key informant interviews with the Directors of the various departments.

b. Co-creation of an OCS implementation plan, which prioritized critical capacity areas with urgent strengthening needs.

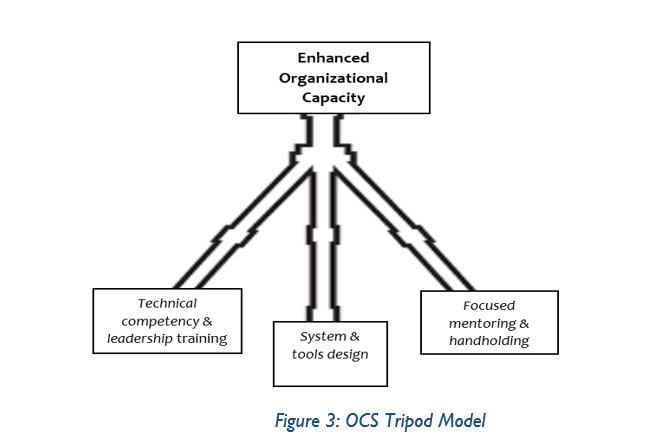

c. Deployment of an OCS tripod model (comprising competency and leadership training, system and tool design, and focused mentoring and handholding) to address the organizational capacity gaps of the agencies.

Key Institutional Capacity Gaps

The organizational capacity assessment revealed several institutional capacity gaps in the SSHIAs and SPHCDAs. Table 1 below summarized the agencies’ key capacity gaps across the 12 OCS dimensions.

Table 1: Summary of key institutional capacity gaps

| S/N | Capacity Dimensions | Capacity Gaps |

| Organizational Development | ||

| 1 | Organizational mandate | Most staff of the agencies do not have adequate knowledge of the mandate of their organization and how it relates to core functions. |

| 2 | Strategy and planning | Lack of capacity to develop a long-term strategy/strategic plan Inadequate capacity to effectively implement strategy and monitor its implementation |

| 3 | Structure and planning | Shortage of staff to perform core organizational functions Weak performance management of existing staff |

| 4 | Implementation capacity | Weak capacity to execute policies, strategies and plans |

| 5 | Leadership and management | Weak internal coordination (particularly, irregular conduct of meetings at all levels) to promote issue-focused decision-making along areas of core mandate |

| 6 | Gender equality and social inclusion | Inadequate knowledge of the GESI concept and its implication for the operation of the agencies Lack of documented policy and plan to guide GESI operationalization and mainstreaming into health insurance and primary healthcare activities. |

| 7 | Resources | Inadequate resources to carry out core activities Inadequate resource mobilization capacity Most of the agencies lack a resource mobilization plan/strategy |

| 8 | Coordination and stakeholder engagement | Inadequate capacity to engage and coordinate stakeholders to effectively harness external opportunities required for operations Lack of structured plan/framework to guide stakeholder coordination |

| 9 | Organizational governance | There is no governing board for oversight and accountability functions in most of the agencies |

| Technical Capacity | ||

| 10 | Technical capacity | SSHIAs: Inadequate staff to support health insurance marketing activities Weak capacity of available staff to perform core health insurance functions (e.g. enrolment, claims management and quality assurance) Lack of a marketing plan/strategy to guide the implementation of health insurance marketing activities SPHCDAs: Outdated Minimum Service Package (MSP) documents to set standards for PHC types Minimal capacity for MSP implementation Lack of a tracking framework for MSP implementation |

| Financial Management, Business Planning, and Compliance | ||

| 11 | Management systems | Lack of functional ICT operating system, financial and HR managements system and capacity |

| 12 | Compliance | Weak system to monitor and ensure adherence with organizational compliance policies. |

Interventions

OCS prioritization principle

The OCS interventions were guided by an organizational capacity strengthening plan developed to bridge the prioritized critical gaps revealed by the organizational capacity assessment. The prioritization of capacity-strengthening interventions is premised on the principle of “understanding the whole while fixing a part and mobilizing those that will fix the rest”. This is based on the understanding that the scope of the project was insufficient to bridge all the identified capacity gaps. Thus, the principle sought to understand the agencies’ capacity gaps across the 12 broad dimensions and strengthen their weak management and core technical practices, while repositioning them for effective partnership and collaboration to harness external opportunities to bridge the other capacity gaps. Hence, five capacity dimensions were prioritized for strengthening. These are (a) management and leadership; (b) partnership and stakeholders’ coordination; (c) GESI; (d) resource mobilization; (d) technical capacity areas of health insurance marketing and communication; and (e) MSP implementation and HRH management (for the SPHCDAs). The OCS interventions were also guided by the core principle of resource optimization, which ensures that the agencies optimize available resources (man, money, materials, and policies) to achieve their mandates. Hence, the prioritization of gaps that will enable the agencies to optimally use their existing resources if bridged.

OCS Approach

An organizational capacity-strengthening tripod model was deployed to address the identified gaps in the prioritized OCS dimensions. The components of the tripod model are illustrated in Figure 2 and described below.

Technical Competency and Leadership Training: The institutional capacity strengthening of the agencies to address the gaps identified across the prioritized dimensions commenced with a combined 4-day competency and leadership training for the SSHIAs and SPHCDAs in each state to deepen the knowledge of the agencies’ staff. The joint training facilitated peer learning and deep discussion of issues and opportunities for effective collaboration to strengthen the demand and supply side of healthcare functions between the two agencies in each state. Also, a leadership capacity strengthening component was included in each capacity training module to position the agencies’ staff to be change agents and work effectively within their teams to translate knowledge and skills into action.

- Systems and tool design: This component of the tripod model focused on developing organizational tools, policies, and guidelines where necessary to guide the operations of the agencies across the capacity-strengthening areas. The Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) developed for the agencies include (a) partnership and stakeholder coordination framework; (b) GESI policy; (c) health insurance marketing and communication plan; and (d) MSP implementation framework.

- Focused mentoring and handholding: Following the capacity strengthening workshops, the agencies were mentored to incorporate the best practices learnt from the capacity building workshop into their operations in the identified areas of gaps. The focused mentoring and handholding activities were implemented simultaneously with the systems and tool development component of the tripod model.

Emerging Results

Following the deployment of the capacity-strengthening tripod model to address the agencies’ prioritized gaps, the following early OCS results have emerged:

a) Enhanced health insurance marketing and enrolment:

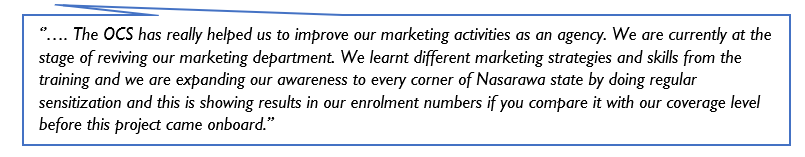

- Deployment of additional staff to the marketing department of the Nasarawa State Health Insurance Agency (NASHIA) from the State Ministry of Commerce as a result of an effective partnership between the two institutions. This helped to increase the enrolment drive and contributed to the increased enrolment recorded

- Review/development of health insurance messaging and IEC materials for the different target audiences as a result of the capacity-building on marketing

- Increased targeted sensitization, awareness creation and advocacies to promote enrolment in the scheme as recommended during the capacity-building workshop

- The actions outlined above led to increased enrolment in NASHIA. Before the OCS intervention in October 2023, NASHIA’s coverage level stood at (159,600) which is 5.7% of the population of Nasarawa State. As a result of strengthening the agency’s marketing capacity, NASHIA recorded a significant increase in enrolment coverage of about 50,000 persons, translating to 206,628 (7.2%) of the state population, most of whom were enrolled from the informal sector. A staff of the agency affirmed this increase in population coverage:

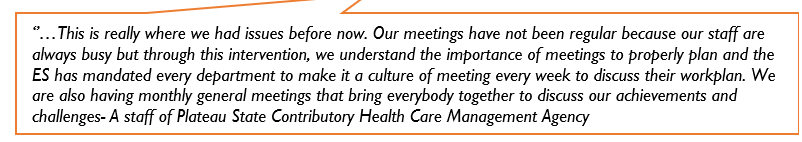

b) Improved management practices and coordination:

- Regular and issue-focused weekly departmental and monthly management meetings to promote effective coordination along areas of core mandates of the agencies. This assertion was corroborated by a respondent from one of the agencies:

- Adoption and use of an effective tool to manage meeting discussions along key objective areas, shifting away from the old practice of using meeting minutes.

c) Improved partnership and stakeholder coordination:

- Holding regular and issue-focused partnership meetings with key stakeholders to discuss possible areas of support to bridge other capacity gaps

- The deployment of NOA’s officers to support health insurance awareness creation at the grassroots as a result of the engagement of the National Orientation Agency (NOA) by the health insurance agency in Nasarawa State

- Partnership with media houses in the states through an MoU to deepen awareness of health insurance alongside other targeted advocacies to individuals, organizations and associations within the states to boost enrolment.

d) GESI

- Designation of a GESI officer in three of the Agencies who were mentored on the implementation of the developed GESI policy.

Lessons Learnt

The key lessons learnt from the implementation of the OCS are as follows:

- The co-creation and participatory approach deployed to identify the capacity gaps and bridge them jointly stimulated ownership by the agencies.

- The combined capacity strengthening workshops organized for the service suppliers and purchasers (i.e., SPHCDAs and SSHIAs, respectively) in each state facilitated peer learning and deeper discussion of issues and opportunities for effective collaboration to strengthen the demand and supply side of healthcare functions.

- The desired impact of capacity strengthening requires time and dedicated effort, such as long-term coaching and mentoring, to fully adopt new practices.

Critical Success Factors

The key factors that contributed to the success of this intervention include:

- Using the OCS prioritization principle to select critical capacity-strengthening areas that required urgent intervention ensured that the identified critical gaps were addressed with the limited resources available.

- Deploying the capacity-strengthening tripod model provided a holistic approach to bridging the prioritized capacity gaps.

- Regular engagement of senior-level Directors of the Agencies, appointed as OCS focal persons, facilitated the identification of OCS successes and challenges, which informed adaptive learning for improvement.

- Consistent coaching and follow-up efforts helped ensure that the agencies adopted new concepts and tools for their operations.

- Co-creation approach to jointly identify and bridge capacity gaps promoted ownership by the agencies.

Recommendations

The lessons learned during the implementation of the OCS have specific implications for future OCS implementation efforts; thus, the following actions are recommended:

- Long-term mentoring and handholding should be incorporated into capacity-strengthening efforts to derive maximum gains, ownership, and sustainability.

- Institutional capacity strengthening should be extended to the institution’s sub-levels that also play key management functions affecting frontline operations.

- Donor support should be solicited by incorporating OCS into their annual project scope to clearly articulate the essential role of capacity strengthening in sustainability and transition beyond their interventions.

Conclusion

The institutional capacity strengthening of the SSHIAs and SPHCDAs in the three states has successfully demonstrated improvement in the agencies’ organizational culture and the adoption of practices that will accelerate progress towards achieving their mandates of expanding coverage and access to healthcare delivery. The tripod approach deployed to address the agencies’ capacity gaps underscores the need for long-term coaching and follow-up efforts to ensure that government institutions fully adopt new concepts and tools for operations and build ownership and sustainability beyond the lifespan of donor-supported projects.

Comments are closed.