Background

Nigeria has a lower life expectancy (54 years) than other African countries, partly due to the country’s high under-5 mortality rate.[1] The Nigeria health sector is characterized by sub-optimal health indices, with a neonatal mortality rate of 34 deaths per 1,000 live births, infant mortality rate of 69 deaths per 1,000 live births, and under-5 mortality rate of 107 deaths per 1,000 live births, which is higher than the Sub Saharan African average of 27 deaths per 1,000 live births, 49 deaths per 1,000 live births, 71 deaths per 1,000 live births respectively.[2] Also, Nigeria’s health outcomes are dismal, and progress is slow. This is partly attributable to suboptimal government spending on health, which was 0.54% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2021[3] – far from the 5% of GDP recommended to accelerate progress towards achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC)[4]. The situation is further compounded by inefficient utilization of the modest resources allocated to health at all levels; this is evidenced by research which revealed that Nigeria’s population health outcomes are poor when compared with countries of similar income levels and equivalent or lower health expenditure in Africa[5]

Considering that primary health care (PHC) is the cornerstone of the overall health system strengthening, the government of Nigeria has developed several policies and interventions to catalyse improved access to PHC services. These include the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), state equity fund, drug revolving fund, PHC Under One Roof, etc. However, the PHC system is yet to perform optimally, partly due to gaps in management of the modest resources available due to inadequate management capacity among the PHC staff.

Efforts geared towards improving the management of Nigeria’s health system have been focused on the health ministries, departments and agencies. Hence, there has been little or no deliberate effort to improve the management capacity of the front-line health workers who are the end users of health resources. This has significantly contributed to inadequate numbers, maldistribution, and a lack of motivation among health workers. It has also led to mismanagement of funds, financial wastages, and stock-out of drugs and essential commodities, impacting access to and the quality of healthcare delivery in the country.

Several studies have established the need for management capacity training for hospital managers in Nigeria because management is not part of the curricula in medical schools.[1],[2] Therefore, the USAID-funded Integrated Health Program (IHP) engaged Development Governance International Consult (DGI Consult) to provide technical support to bridge the management capacity gaps of selected healthcare workers in the Federal Capital Territory using the Facility and Financial Management (FFM) toolkit developed by the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) with the support of IHP.

Approach

To tackle the deficiencies in management capacity and enhance PHC delivery, DGI Consult implemented a FFM capacity development project in the FCT. The beneficiaries include Officers-In-Charge (OICs), Finance Clerks, and Ward Development Committee (WDC) members of the 70 first-generation USAID IHP-supported primary healthcare facilities across the 6 area councils in FCT. The FFM capacity development was deployed from a sustainability perspective, with consideration for gender equality and social inclusion. The capacity-building initiative involved implementing the activities outlined below.

- State-level training of 20 trainers selected from the state and area council government health parastatals to equip them with the necessary skills to cascade the FFM training to selected PHC management teams and establish a pool of FFM trainers in the FCT.

- Area Council-level training of 210 management team members (i.e., OICs, finance clerks, and WDCs) from 70 USAID IHP-supported facilities. The training covered modules on PHC governance, financial management, human resources, drugs and consumable management, and monitoring and supportive supervision.

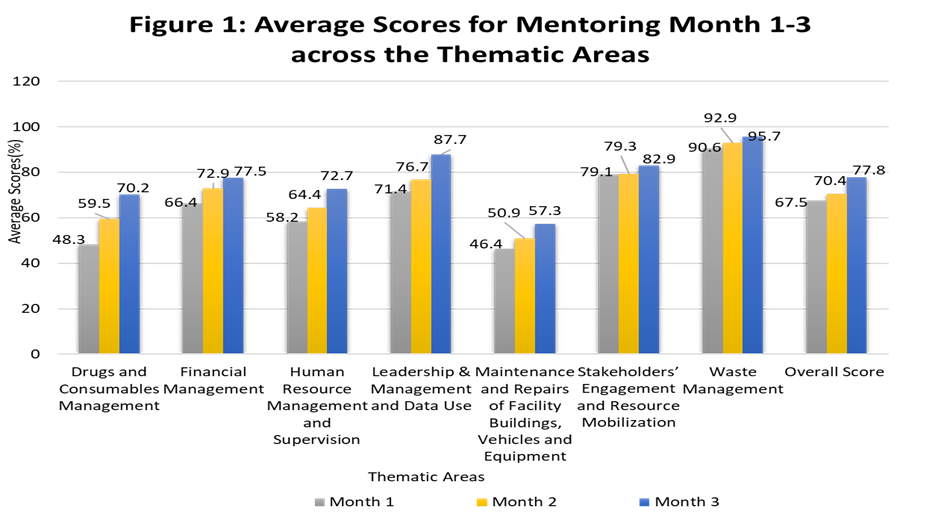

III. Post-training monthly mentoring visits to each of the 70 PHCs for three consecutive months to assess the implementation of the FFM best practices learned and provide on-the-job training where necessary.

The mentoring was conducted in accordance with the mentoring guide developed for the activity. A checklist was used to assess the facilities’ performance across seven thematic areas including (a) Drugs and Consumables Management; (b) Financial Management; (c) Human Resources Management; (d) Leadership & Management and Data Use; (e) Stakeholder Engagement and Resource Mobilization, (f) Maintenance and Repairs of Facility Buildings, Vehicles and Equipment; and (g) Waste Management. The facilities’ performance (in the form of scores) was recorded on Open Data Kit (ODK) and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office 365). The parameters assessed across the seven thematic areas are attached as Annex 1.

Results

Majority (96%) of the participants acquired additional knowledge on Facility and Financial Management during the training, this is evidenced by the increase in knowledge on the subject from an average pre-test score of 63.3% to an average post-test score of 80.7%, with a mean knowledge gain of 17.5 percentage points ranging from 5-60 percentage point gain among the participants. In addition, module evaluations indicated that most of the participants acquired new knowledge, attitudes, and skills from the training program.

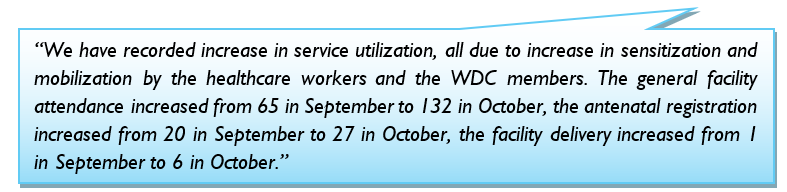

As observed during the mentoring visits, the training and follow-on handholding significantly improved the trainees’ management capacity across the 70 facilities. The improvements are evidenced by the progressive increase in performance scores for the seven thematic areas of mentoring across the three cycles of monthly mentoring visits, as shown in Figure 1 below. Also, the monthly average mentoring scores increased from 67.5% in month 1 to 70.4% in month 2 and 77.8% in month 3 of mentoring. There was remarkable improvements in drugs and consumables management, financial management and human resource management. Stakeholders’ engagement and resource mobilization, and waste management recorded the least improvement.

In addition to the improved performance scores, specific operational improvements were recorded at the end of the mentoring visits. Below are some of the areas where improvement was recorded in many of the facilities.

- The WDC mobilized resources for infrastructure development and engagement of volunteer health workers, which has aided service availability, particularly the provision of 24-hour services in many facilities.

- The facility staff and WDC started collaborating more effectively, aiding increased awareness of the proper health-seeking behaviour in the communities, which resulted in increased demand for and the uptake of health services. The OIC of Kiyi PHC recounted:

3. The facility staff can now develop and adequately use human resource for health management tools such as updated and displayed organogram, updated duty rosters, handover notes, etc. This has led to the effective implementation of the task shifting and sharing policy and increased productivity of the health workers.

4. The facilities’ drug and consumables management, such as proper use of bin cards and daily consumption registers has improved. This has solved the issue of stock-out of the 13 life-saving essential drugs.

5. The facilities’ financial management has improved due to accurate financial record keeping and the use of appropriate financial tools. Some OICs corroborated it:

Critical Success Factors

The key factors that contributed to the success of this intervention include:

- The availability of a national facility and financial management toolkit enabled high-quality delivery of the FFM capacity building.

- The choice of trainers, i.e., government officials who are familiar with the context of the FCT health system and are responsible for supervising the facilities contributes to the program’s sustainability.

- Flexibility in the program approach helped to ensure that all 70 facilities participated in the mentoring despite the security challenges experienced in some areas.

- Mentoring and handholding for three consecutive months helped to institutionalize best practices in the PHCs.

- Adaptive learning during implementation helped to manage the challenges encountered. For instance, the review meetings held during mentoring exercises to appraise the mentoring process and agree on improvement strategies helped improve the quality of mentoring over time.

Recommendations

To sustain the gains of the FFM capacity development and further augment the delivery of PHC in Nigeria, the following actions are proposed:

- There should be deliberate efforts to mobilize resources to scale up the FFM capacity building nationwide.

- The FFM capacity building should be included in the Annual Operational Plans of the State Primary Health Care Boards/Agencies, and funds should be allocated to the activity in states’ annual budgets. Private Sector and donor funding can also be leveraged to implement the program.

- The State Primary Health Care Boards/Agencies should coordinate capacity building for health workers to avoid duplication and frequent unavailability of health workers in the facilities due to multiple trainings.

- The FFM training toolkit and capacity-building process should be periodically reviewed to conform with current health policies and priorities.

- The FFM training modules should be incorporated into the pre-service curriculum of health training institutions.

- The NPHCDA should digitize the FFM toolkit (as online training/course) for easy access and work with health regulatory bodies to ensure that it counts as Continuing Medical Education points tied to license renewal.

Conclusion

This Facility and Financial Management program, enabled by USAID Integrated Health Program Nigeria and delivered by DGI Consult, has successfully developed the capacity of healthcare workers for sustainable advancement of PHC service delivery in the FCT. The observed improvements in PHC functions across key thematic areas underscore the importance of management capacity building for frontline health workers. Mentoring and handholding will be more effective if implemented over a long period; they will ensure the institutionalization and sustainability of the best practices adopted by the PHCs.

Annex 1: Parameters Assessed across the 7 Thematic Areas of Mentoring

1. Drugs and Consumables Management

- Availability of designated pharmacy technician

- Availability of updated inventory control cards for each commodity

- Availability of essential drugs in the pharmacy

- Availability of updated Daily Consumption Register

- Drug and consumable stock needs for the facility calculated correctly

- Monitoring and recording of temperature records for the facility’s drug store and refrigerator consistently

- Availability of updated expired drug registers

- Stock out of any of the 13 life-saving essential commodities

- Availability of updated Store Ledger/Stock Records

- Availability of stock below re-order level

- Availability of evidence of cashbook reviews in practice

- Availability of Bank Reconciliation statement for the previous month

- Availability of Monthly expenditure report for the previous month

- Availability and evidence of use of payment vouchers

- Availability of evidence of the use of the following supporting documents (PVs, invoices, receipts, approved requests) correctly filed and attached to payment vouchers

- Availability of the most recent quarterly business plan prepared, submitted and approved by the PHCB

- Availability of evidence of WDC review and feedback on the PHC’s business plan

- Availability of receipts of commodity and consumable procurement for the facility

- Evidence of supply procurement with date of procurement

- Availability of updated fixed asset register

- Record of the different sources of the facility income

- Availability of up-to-date records of Facility expenditure and income

3. Human Resource Management

- Availability of PHC duty rosters pasted on the wall

- Availability of practice of “task shifting” at the facility (e.g. CHEWs/CHOs trained and providing LARC and or conducting deliveries as SBAs)

- Availability of staff job description

- Evidence of staff performance assessment conducted at least one time in a year

- Availability of LGHA plan for staff in-service training

- Availability of staff training record book

- Availability of list of staff training in the last six month

4. Leadership & Management and Data Use

- Existence of the annual quality improvement plan (QIP) that encompasses all the activities in the PHC basic minimum package of services?

- Existence of a fully completed quarterly business plan with activities derived from the QIP

- Existence of a fully completed quarterly business plan with activities derived from the QIP

- Availability of facility goal and plan set for itself for the period of mentoring

- Evidence of delegation of duty during the previous month (e.g. job assignments that are outside the job description or job position of staff, representation of the OIC in meetings or trainings as appropriate, other staff chairing the FMC meetings etc.)

- Availability of the list of activities or tasks to be done at the facility available

- Availability of documented priorities set for the month of visit

- Awareness of facility staff on the priorities set for the month

- Evidence of tracking and measuring outputs or results of tasks and activities planned at the facility

- Availability of updated facility organogram displayed at the facility

- Evidence of the use of facility service delivery data for planning and management decision-making

5. Stakeholders’ Engagement and Resource Mobilization

- Regularity of WDC meetings

- Regularity of Facility Management Committee (FMC) meetings

- Evidence of use of service delivery data at WDC and FMC meetings

- Evidence of use/review of financial data at WDC and FMC meetings

- Availability of set targets and objectives for community engagements, such as mobilization and sensitization about increasing service utilization, PHC revitalization, philanthropists’ engagement, immunization targets, community outreach, etc.

- Availability of a mechanism for receiving and handling feedback from patients/clients after services at the facility

- Evidence of instances of issues identified and addressed at the facility after the patients/clients’ feedback

- Availability of evidence of resources mobilized from the community during the past 3 months/quarter

6. Maintenance and Repairs of Facility Buildings, Vehicles and Equipment

- Availability of updated assets inventory list that provides the location and condition of each inventory item

- Availability of a vehicle

- Availability of a vehicle logbook in PHCs that have vehicles

- Existence of a vehicle logbook that is completely filled out and up to date

- Completion of Vehicle maintenance

- Evidence of preventive maintenance checklist completed

- Availability of PHC maintenance budget, which is included in the facility business plan, released and utilized.

7. Waste Management

- Practice of segregation and disposal of waste at the facility

- Availability of sharp boxes in every service delivery point, including the lab, FP room, immunization room/areas, labour room, injection room, etc.

- Practice of sharp box disposal as per protocol

- Availability and use of color-coded bins and liners for segregation of wastes

References

[1] Ochonma, O. G., & Nwatu, S. I. (2018). Assessing the predictors for training in management amongst hospital managers and chief executive officers: a cross-sectional study of hospitals in Abuja, Nigeria. BMC medical education, 18, 1-11.

[2] Adindu, A. (2013). Management training and health managers perception of their performance in Calabar, Nigeria. Manage Health, 17, 14-19.

[3]Abubakar, I., Dalglish, S. L., Angell, B., Sanuade, O., Abimbola, S., Adamu, A. L., … & Zanna, F. H. (2022). The Lancet Nigeria Commission: investing in health and the future of the nation. The Lancet, 399(10330), 1155-1200.

[4] World Bank Open Data (2022). Accessed at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.NMRT, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT

[5]World Bank Open Data (2021). Accessed at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.GHED.GD.ZS?locations= NG

[6] Mcintyre, D., Meheus, F., & Røttingen, J. A. (2017). What level of domestic government health expenditure should we aspire to for universal health coverage? Health Economics, Policy and Law, 12(2), 125-137.

[7] Angell, B., Sanuade, O., Adetifa, I. M., Okeke, I. N., Adamu, A. L., Aliyu, M. H., … & Abubakar, I. (2022). Population health outcomes in Nigeria compared with other west African countries, 1998–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet, 399(10330), 1117-1129.

Comments are closed.